Clarissa Wern Ting Wong is one of our 2020 winners for the HIEEC.

The economist Keynes once posited that when the quantitative calculation of expected utility can hardly help us make a decision, it is our “animal spirits” – or emotional states – that kick in and urge us into action (Keynes, 1936). This surmise proved prescient. From unbridled optimism that fuels an economic bubble, to stubbornness that undermines policies meant to raise social welfare, many suboptimal decision patterns that repeat themselves throughout history can be attributed to people’s “irrational” sides getting the better of them (Akerlof et al., 2009).

How We Make Suboptimal Decisions

A rational economic agent acting in accordance with expected utility theory is expected to evaluate a set of perfect information using mathematical logic: He calculates the utility he could gain from each option. Then, he chooses the option that maximises his utility within his budget constraints. However, real-life decisions are not informed purely by such mathematical calculations, but also by heuristics, biases and misconceptions which make us imperfect decision-makers.

Heuristics are mental shortcuts that people use to save time and mental effort in decision-making. Using these heuristics sometimes leads to statistically systematic errors in one’s information processing, also known as cognitive biases. For example, people tend to form an impression based on only a few salient examples that come to mind. This leads to the availability bias, whereby a minority of salient information disproportionately influences one’s judgement on the probability of something happening (Thaler, 2009). Resultant distortions in people’s probability judgements can lead them to make suboptimal decisions. For example, influenced by the preceding bull run in Internet stocks and the palpable optimism of fellow investors, investors in the 1990s came to display “irrational exuberance” in their expectations (Greenspan, 1996) and grossly overvalued Internet stocks. Energy consumers, on the other hand, tend to overconsume energy when they are not provided salient information like their level of energy usage (Thaler, 2009). People make suboptimal decisions when they over- or under-estimate an action’s utility: In one instance, important but non-salient information, like energy usage, is ignored; In another instance, salient but unrepresentative information, like overoptimistic expectations, is used to form the big picture.

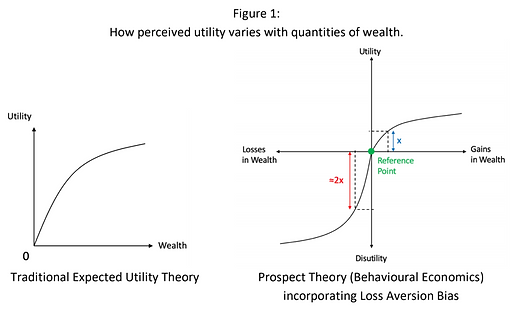

Other cognitive biases can similarly distort one’s ability to make rational decisions. People tend to feel losses (shown as the red arrow in Figure 1) about twice as hard as gains (shown as the blue arrow) for the same change in wealth from a reference point (Tversky et. al, 2000). This leads them to exhibit loss aversion bias.

Loss aversion bias has been used to explain the endowment effect, where people tend to value goods they own higher than an identical good they do not own (Thaler, 2015). This is because they likely overvalue their loss in utility should they give up what they own. Consequences can be serious: If policymakers exhibit sufficient loss aversion, they may overprotect loss-making sectors, or develop anti-trade biases (Tovar, 2009).

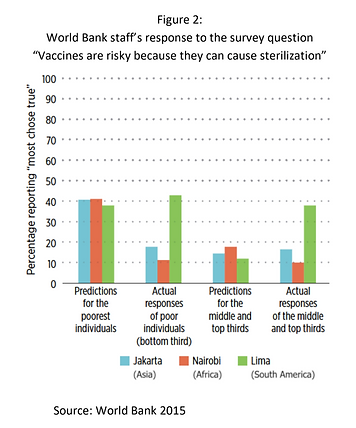

Besides cognitive biases, misconceptions can also influence suboptimal decision making. As shown in Figure 2 below, World Bank development staff were generally shown to have believed that the poor were more suspicious of vaccines that they actually were. If such biases form assumptions in models which are used to predict an audience’s vaccine receptivity, this could lead to suboptimal allocation of resources for health outreach initiatives.

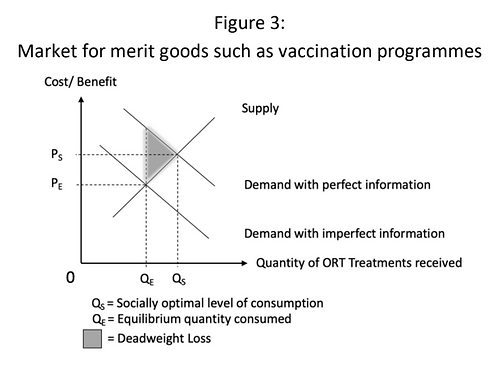

Separately, public health beneficiaries in developing countries can also hold misconceptions that impede policymakers’ efforts. In a South Asian nation, 35-50% of poor, lesser-educated women wrongly perceived the appropriate treatment for diarrhoea to be a reduction of water intake (World Bank, 2015). In fact, rehydration of the body is essential to treat diarrhoea. This caused the beneficiaries to undervalue the utility of the Oral Rehydration Therapy (ORT) programme, and thus under-consume it. Committing to misconceptions that are prevalent in a certain society can cause people to make suboptimal judgements.

Hitherto, we have discussed how biases, heuristics and misconceptions affect both governor and governed, both buyer and seller. If these factors result in suboptimal decision making, one forgoes the opportunity to choose an alternative option that would have yielded greater utility in the long run – avoiding over-buying inflated stocks, saving energy, bettering trade policies or receiving healthcare treatment.

The prevalence of sub-optimal decision-making implies that the application of traditional economic theory is limited in the real world. General Laws like the Law of Supply and Demand logically optimise resource allocation, but only if one makes rational choices. Influenced by a multitude of biases and heuristics and egged on by the lightning-speed pace of information spread, people inevitably make irrational choices. In the past, news of the Titanic’s sinking took hours to reach news outlets. Today, online tweets and posts make information, both real and fake, available instantaneously. Traders across the globe may be triggered to make knee-jerk, heuristic-influenced trading decisions. This increases the chance that market prices may overshoot their true value.

.....

篇幅有限,扫码即可免费获取完整版论文pdf